Beyond the Checkbox: on Accessibility, with Gertie

A couple of weeks ago, I was reading about Thinking Machines Lab, an AI research and product company built by Mira Murathi, the former CTO of OpenAI, whose mission is to develop top-notch AI to make it useful and accessible. Murati sees a significant gap between the rapid advancements in AI and the public’s understanding of the technology. Thinking Machines Lab aims to bridge this divide by building in and prioritising accessibility from the outset.

This made me think a lot about accessibility and what it would look like in the next set of tools, platforms, and products being built in the industry. This sort of led me into a conversation with my friend, Gertie Nyenyeshi, an Accessibility champion who has spent the last couple of years promoting, teaching and building a community in East Africa, via her community A11y Africa, around building accessibility into digital products.

Let’s jump in!

Accessibility is about creating digital experiences for people with disabilities, including those who are blind, deaf, or have other impairments. Gertie became interested in it while working as a web developer at the BBC in 2018. During onboarding, an accessibility specialist gave a presentation that introduced her to the concept. At that point, she had been in tech for about three years, yet accessibility had never been part of her training.

“We were taught how to build web experiences, but never discussed users with disabilities.

This became personal for me because being a woman in tech is already challenging, and I saw another marginalised group being overlooked. Everyone deserves equal access to the web, and I wanted to make a difference. Additionally, as a Black person, I was already aware of how technology, particularly AI, can exclude certain groups. I realized I had a voice in this space and decided to use it by building a community and teaching others how to create accessible digital experiences.

My focus on front-end development deepened my commitment, as I work directly with user experiences. People with disabilities are users too, and it’s essential to design with them in mind.”

Of course, we know AI now allows developers to generate code effortlessly, even creating entire websites. However, these AI-generated experiences often lack proper accessibility. This issue stems from the training data, which includes minimal accessibility information, largely reflecting the real-world landscape where boot camps, tutorials, and blog posts rarely emphasize accessibility.

While AI does present challenges in this area, there are also promising accessibility solutions being developed. For example, some researchers and engineers, including those at Microsoft, are exploring AI-driven tools for users with disabilities. Though specific examples may not always be widely known, efforts are underway to improve inclusivity.

Ultimately, AI tools require knowledgeable developers who understand accessibility to guide and refine their outputs. Without this expertise, AI can introduce errors and reinforce existing gaps rather than bridging them.

As Gertie and I discussed AI and Accessibility, I started to think about Accessibility from the industry-specific POV. Wondering how much of the concept differs from one aspect of the industry to another. For example, Project Nemo is a campaign to accelerate disability inclusion in the UK fintech industry, while JBL’s Quantum Guide Play allows visually impaired gamers to play first-person shooter games.

For Gertie, Accessibility issues are not unique to any one industry—whether in FinTech, education, or other sectors, digital products often share the same underlying structures. “A poorly designed form, for example, remains inaccessible regardless of where it is used. The challenge lies with the developers and designers who create these products, not necessarily the industries themselves”.

And beyond my tendency to look for specific problems, I agree with her.

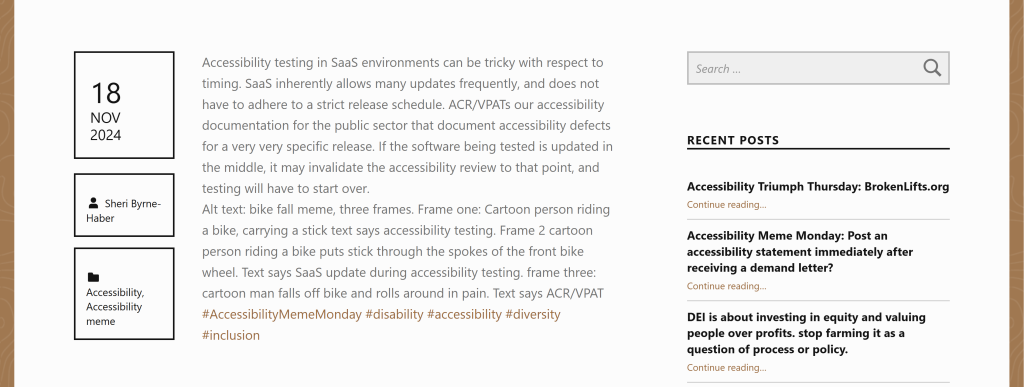

Like Sheri Byrne-Haber mentioned in her post on Accessibility testing in SaaS environments being tricky with respect to timing.

Beyond AI, other emerging technologies like Web3, IoT, and virtual reality (VR) also raise accessibility concerns. “VR, for instance, is heavily used in gaming, where accessibility is an ongoing discussion. Some experts are working to improve inclusivity in this space, though progress varies. In the UK and US, legal frameworks like the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and upcoming European regulations require digital products to meet accessibility standards. Companies that fail to comply can face legal consequences—Netflix, for example, was sued for a lack of subtitles, which led to improved accessibility across streaming platforms.”

In Africa, however, accessibility remains a much bigger challenge. Many digital products lack accessibility features, and there are still ongoing efforts to establish strong policies and regulations. This reflects a broader issue—physical infrastructure is often not built with people with disabilities in mind, making daily life even more difficult. The gap in digital accessibility is just another layer of exclusion.

Addressing these challenges requires both policy-driven solutions and a shift in how products are designed from the start, ensuring that no one is left behind.

How then should we think about accessibility in extremely vulnerable countries, dealing with wars, etc?

In war-torn regions, accessibility and even access to education often take a backseat to survival. When basic needs like food, shelter, and safety are uncertain, there’s little opportunity to build communities, share knowledge, or learn new skills. Without stability, access to information and the ability to create inclusive solutions become severely limited.

In conclusion

Accessibility isn’t a single checkbox or a one-time fix, it’s an evolving practice embedded in every layer of the digital world. From AI-generated code to fintech solutions and VR gaming, accessibility concerns show up everywhere. But at its core, the issue isn’t just about technology; it’s about the people who build it. The biases, gaps, and oversights of developers, designers, and decision-makers shape whether digital spaces are inclusive or exclusionary.

As Gertie highlighted, a poorly designed form remains inaccessible, no matter the industry. The same principle applies to AI, Web3, and any new technology that emerges. The question isn’t just, “Will this tool be innovative?” but also, “Who is it leaving behind?”

In regions like Africa, where accessibility conversations are still gaining momentum, there’s an opportunity to build inclusivity into digital products from the ground up, rather than retrofitting accessibility after the fact. Stronger policies will help, but real change begins with awareness and intention.

The future of accessibility isn’t just about compliance or legal consequences. It’s about designing a digital world where everyone, regardless of ability, can participate fully. Whether you’re a developer, a founder, or an advocate, you have a role to play in peeling back the layers of exclusion and rebuilding with inclusivity at the centre.

No Comments